These assessment and treatment recommendations represent a synthesis of information derived from personal clinical experience and from the numerous sources which are cited, or are based on the work of researchers, clinicians and therapists who are named (Basmajian 1974, Cailliet 1962, Dvorak & Dvorak 1984, Fryette 1954, Greenman 1989, 1996, Janda 1983, Lewit 1992, 1999, Mennell 1964, Rolf 1977, Williams 1965).

Table of Contents

Clinical Application of Neuromuscular Techniques: Hamstrings

Should obviously tight hamstrings always be treated? Van Wingerden (1997), reporting on the earlier work of Vleeming (Vleeming et al 1989), states that both intrinsic and extrinsic support for the sacroiliac joint derives in part from hamstring (biceps femoris) status. Intrinsically the influence is via the close anatomical and physiological relationship between biceps femoris and the sacrotuberous ligament (they frequently attach via a strong tendinous link): ‘Force from the biceps femoris muscle can lead to increased tension of the sacrotuberous ligament in various ways. Since increased tension of the sacrotuberous ligament diminishes the range of sacroiliac joint motion, the biceps femoris can play a role in stabilisation of the SIJ.’

He also notes that in low back patients, forward flexion is often painful as the load on the spine increases. This happens whether flexion occurs in the spine or via the hip joints (tilting of the pelvis). If the hamstrings are tight and short they effectively prevent pelvic tilting. ‘In this respect, an increase in hamstring tension might well be part of a defensive arthrokinematic reflex mechanism of the body to diminish spinal load.’ If such a state of affairs is longstanding, the hamstrings (biceps femoris) will shorten, possibly influencing sacroiliac and lumbar spine dysfunction.

The decision to treat tight (‘tethered’) hamstrings should therefore take account of why it is tight, and consider that in some circumstances it might be offering beneficial support to the SIJ or be reducing low back stress.

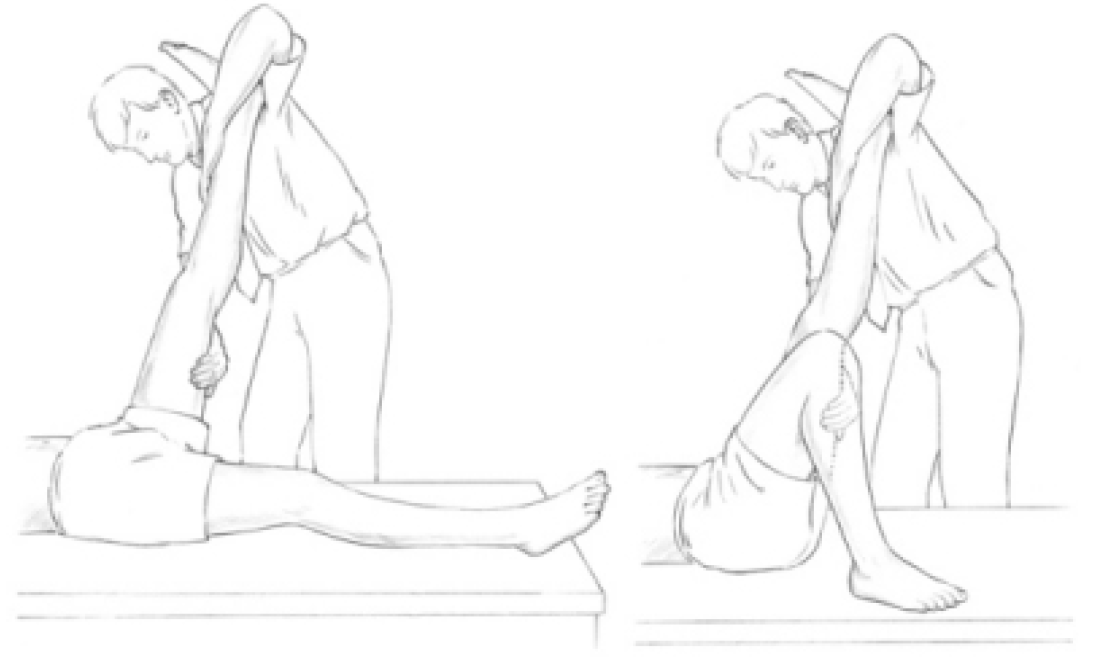

Assessment for Shortness in Hamstrings (Fig. 4.12A, B)

If the hip flexors (psoas, etc.) have previously tested as short, then the test position for the hamstrings needs to commence with the non-tested leg flexed at knee and hip, foot resting flat on the treatment surface to ensure full pelvic rotation into neutral (as in Fig 4.12B). If no hip flexor shortness was observed, then the non-tested leg should lie flat on the surface of the table.

Figure 4.12 (A) Assessment for shortness in hamstring muscles. The practitioner’s right hand palpates for bind/the first sign of resistance, while the left hand maintains the patient’s knee in extension. (B) MET treatment of shortened hamstrings. Following an isometric contraction, the leg is taken to or through the resistance barrier (depending on whether the problem is acute or chronic).

Hamstring test (a) The patient lies supine with non-tested leg either flexed or straight, depending on previous test results for hip flexors. The tested leg is taken into a straight leg raised (SLR) position, no flexion of the knee being allowed, with minimal force employed. The first sign of resistance (or palpated bind) is assessed as the barrier of restriction. If straight leg raising to 80° is not easily possible, then there exists some shortening of the hamstrings and the muscles can be treated in the leg straight position (see below).

Hamstring test (b) (Fig. 4.13) Whether or not an 80° elevation is easily achieved, a variation in testing is also needed to evaluate the lower fibres. To make this assessment the tested leg is taken into full hip flexion (helped by patient holding upper thigh with both hands (see Fig. 4.13). The knee is then straightened until resistance is felt or bind is noted by palpation of the lower hamstrings.

Figure 4.13 Assessment and treatment position for lower hamstring fibres.

If the knee cannot straighten with the hip flexed, this indicates shortness in the lower hamstring fibres and the patient will report a degree of pull behind the knee and lower thigh. Treatment of this is carried out in the test position. If, however, the knee is capable of being straightened with the hip flexed, having previously not been capable of achieving an 80° straight leg raise, then the lower fibres are cleared of shortness and it is the upper fibres of hamstrings which require attention using MET, working from the SLR test position.

Hamstring test (c) Lewit (1999) describes a functional test (see also Fig. 5.10B) which helps to screen for overactivity in the erector spinae and/or hamstrings, indicating also weakness of gluteus maximus. The patient is prone and the practitioner places palpating hands on the lower buttock/upper thigh (gluteal/hamstring contact) and the low back (erector spinae contact) as the patient is asked to extend the hip, leg kept straight.

The normal sequence is for the hamstrings to commence the elevation of the thigh with almost instant gluteal involvement, followed by the erectors. If gluteus maximus is weak (see lower crossed syndrome notes in Ch. 2) there may still be strong extension of the thigh, but with the hamstrings and erectors doing most of the work. This is an indication of overactivity (i.e. stress) in these postural muscles and therefore suggests shortness. In extreme cases the movement of thigh/hip extension is initiated by the erector spinae themselves, and these are then almost certainly short.

MET for Shortness of Lower Hamstrings

If the lower hamstring fibres are implicated as being short (see hamstring test (b) above), then the treatment position is identical to the test position. This means that the non-treated leg needs to be either flexed or straight on the table, depending upon whether hip flexors have previously been shown to be short or not (see above), and the treated leg needs to be flexed at both the hip and knee, and then straightened by the practitioner until the restriction barrier is identified (one hand should palpate the tissues behind the knee for sensations of bind as the lower leg is straightened).

Depending upon whether it is an acute situation or a chronic problem, the isometric contraction against resistance is introduced at this ‘bind’ barrier (if acute) or a little short of it (if chronic). The instruction might be something such as ‘try to gently bend your knee, against my resistance, starting slowly and using only a quarter of your strength’. (It is particularly important with the hamstrings to take care regarding cramp, and so it is suggested that no more than 25% of patients’ effort should ever be used during isometric contractions in this region.)

Following the 7–10 seconds of contraction (holding the breath if possible, see Box 4.2) followed by complete relaxation, the leg should, on an exhalation, be straightened at the knee towards its new barrier (in acute problems) and through that barrier, with a degree of stretch (if chronic), with the patient’s assistance. This slight stretch should be held for not less than 10 (and up to 30) seconds.

Repeat the process until no further gain is possible (usually one or two repetitions achieve the maximum degree of lengthening available at any one session). Antagonist muscles can also be used isometrically by having the patient try to extend the knee during the contraction rather than bending it, followed by the same stretch as would be adopted if the agonist (affected muscle) had been employed.

MET for Shortness of Upper Hamstrings

If the upper fibres are involved (i.e. hamstring test (a) above), then treatment is performed in the straight leg raised (SLR) position, with the knee maintained in extension at all times. The other leg should be flexed at hip and knee or straight, depending on the hip flexor findings as explained above. In all other details the procedures are the same as for treatment of lower hamstring fibres except that the leg is kept straight.

Alternative Methods

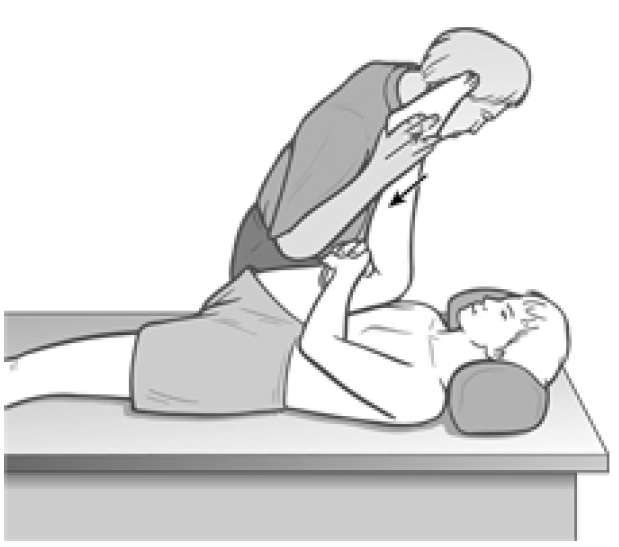

An alternative position for treatment of hamstrings is for the supine patient to flex the affected hip fully. The flexed knee is extended by the practitioner to the point of resistance (identifying the barrier). The calf of the lower leg is placed on the shoulder of the practitioner, who stands facing the head of the table on the side of the treated leg.

If the right leg of the patient is being treated, the calf will rest on the practitioner’s right shoulder, and the practitioner’s right hand stabilises the patient’s extended unaffected leg against the table. The practitioner’s left hand holds the treated leg thigh to both maintain stability and to palpate for bind when the barrier is being assessed. The patient is asked to attempt to straighten the lower leg (i.e. extend the knee) utilising the antagonists to the hamstrings, employing 20% of the strength in the quadriceps. This is resisted by the practitioner for 7–10 seconds. Appropriate breathing instructions should be given (see notes on breathing, Box 4.2). The leg is then extended at the knee to its new hamstring limit if the problem is acute (or stretched slightly if chronic) after relaxation and the procedure is then repeated.

Or

In this same position, the patient may attempt to flex the knee against resistance, thus employing the hamstrings isometrically for 7–10 seconds (with appropriate breathing, see Box 4.2). After relaxation, the muscles are taken further to or through their new barrier (depending upon whether the problem is acute or chronic).

Or

Starting from the same position, a combined contraction may be introduced (Moore et al 1980). The instruction to the patient would be to pull the thigh towards her own face (i.e. to flex the hip) and to push the lower leg downward onto the practitioner’s shoulder (i.e. flexing the knee). This effectively contracts both the quadriceps and the hamstrings, thus inducing both postisometric relaxation and reciprocal inhibition, which facilitates, on an exhalation, subsequent easing to, or stretching through, the restriction barrier of the tight hamstrings.

Dr. Alex Jimenez offers an additional assessment and treatment of the hip flexors as a part of a referenced clinical application of neuromuscular techniques by Leon Chaitow and Judith Walker DeLany. The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic and spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

By Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Wellness

Overall health and wellness are essential towards maintaining the proper mental and physical balance in the body. From eating a balanced nutrition as well as exercising and participating in physical activities, to sleeping a healthy amount of time on a regular basis, following the best health and wellness tips can ultimately help maintain overall well-being. Eating plenty of fruits and vegetables can go a long way towards helping people become healthy.

WELLNESS TOPIC: EXTRA EXTRA: Managing Workplace Stress

Post Disclaimer

Professional Scope of Practice *

The information on this blog site is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified healthcare professional or licensed physician and is not medical advice. We encourage you to make healthcare decisions based on your research and partnership with a qualified healthcare professional.

Blog Information & Scope Discussions

Welcome to El Paso's Premier Wellness and Injury Care Clinic & Wellness Blog, where Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, FNP-C, a board-certified Family Practice Nurse Practitioner (FNP-BC) and Chiropractor (DC), presents insights on how our team is dedicated to holistic healing and personalized care. Our practice aligns with evidence-based treatment protocols inspired by integrative medicine principles, similar to those found on this site and our family practice-based chiromed.com site, focusing on restoring health naturally for patients of all ages.

Our areas of chiropractic practice include Wellness & Nutrition, Chronic Pain, Personal Injury, Auto Accident Care, Work Injuries, Back Injury, Low Back Pain, Neck Pain, Migraine Headaches, Sports Injuries, Severe Sciatica, Scoliosis, Complex Herniated Discs, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Pain, Complex Injuries, Stress Management, Functional Medicine Treatments, and in-scope care protocols.

Our information scope is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, physical medicine, wellness, contributing etiological viscerosomatic disturbances within clinical presentations, associated somato-visceral reflex clinical dynamics, subluxation complexes, sensitive health issues, and functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions.

We provide and present clinical collaboration with specialists from various disciplines. Each specialist is governed by their professional scope of practice and their jurisdiction of licensure. We use functional health & wellness protocols to treat and support care for the injuries or disorders of the musculoskeletal system.

Our videos, posts, topics, subjects, and insights cover clinical matters and issues that relate to and directly or indirectly support our clinical scope of practice.*

Our office has made a reasonable effort to provide supportive citations and has identified relevant research studies that support our posts. We provide copies of supporting research studies available to regulatory boards and the public upon request.

We understand that we cover matters that require an additional explanation of how they may assist in a particular care plan or treatment protocol; therefore, to discuss the subject matter above further, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC, or contact us at 915-850-0900.

We are here to help you and your family.

Blessings

Dr. Alex Jimenez DC, MSACP, APRN, FNP-BC*, CCST, IFMCP, CFMP, ATN

email: [email protected]

Licensed as a Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) in Texas & New Mexico*

Texas DC License # TX5807

New Mexico DC License # NM-DC2182

Licensed as a Registered Nurse (RN*) in Texas & Multistate

Texas RN License # 1191402

ANCC FNP-BC: Board Certified Nurse Practitioner*

Compact Status: Multi-State License: Authorized to Practice in 40 States*

Graduate with Honors: ICHS: MSN-FNP (Family Nurse Practitioner Program)

Degree Granted. Master's in Family Practice MSN Diploma (Cum Laude)

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card

Comments are closed.