These assessment and treatment recommendations represent a synthesis of information derived from personal clinical experience and from the numerous sources which are cited, or are based on the work of researchers, clinicians and therapists who are named (Basmajian 1974, Cailliet 1962, Dvorak & Dvorak 1984, Fryette 1954, Greenman 1989, 1996, Janda 1983, Lewit 1992, 1999, Mennell 1964, Rolf 1977, Williams 1965).

Table of Contents

Clinical Application of Neuromuscular Techniques: Piriformis

Assessment of Shortened Piriformis

Test (a) Stretch test. When short, piriformis will cause the affected side leg of the supine patient to appear to be short and externally rotated. With the patient supine, the tested leg is placed into flexion at the hip and knee so that the foot rests on the table lateral to the contralateral knee (the tested leg is crossed over the straight non-tested leg, in other words as shown in Fig. 4.17). The angle of hip flexion should not exceed 60° (see notes on piriformis in Box 4.6).

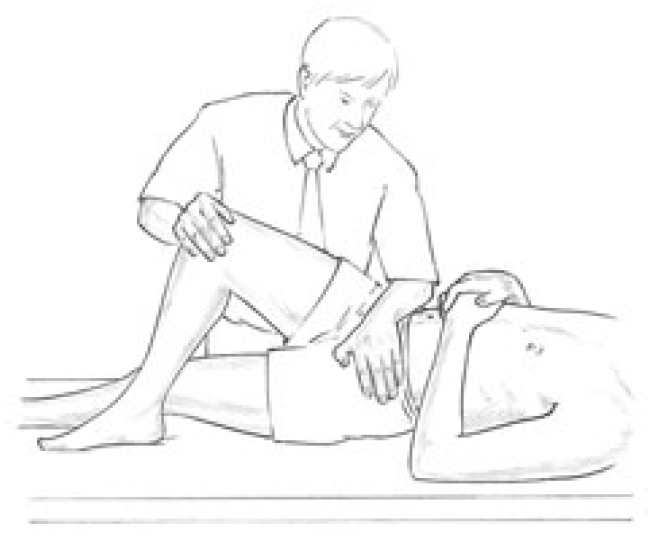

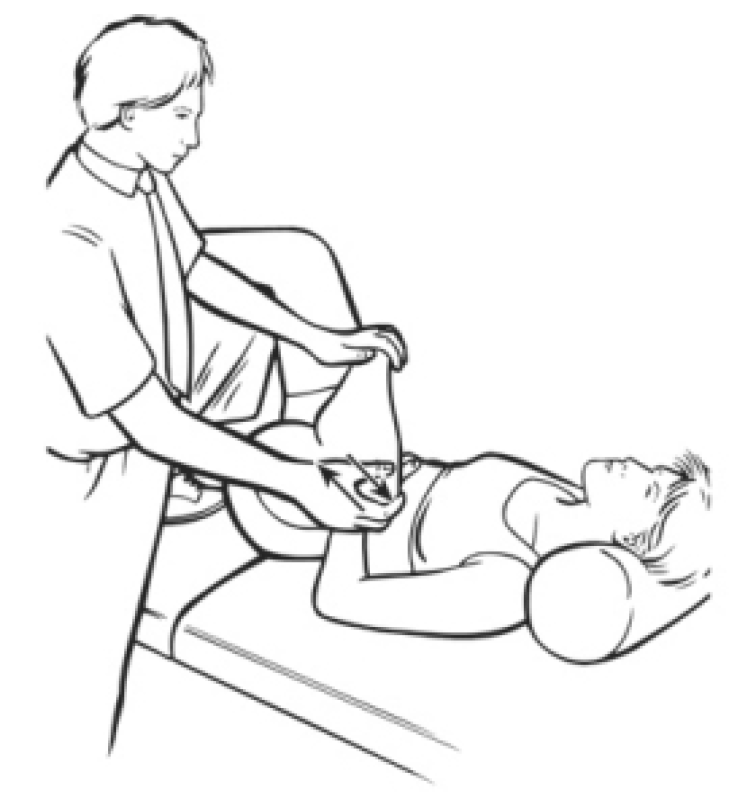

Figure 4.17 MET treatment of piriformis muscle with patient supine. The pelvis must be maintained in a stable position as the knee (right in this example) is adducted to stretch piriformis following an isometric contraction.

The non-tested side ASIS is stabilised to prevent pelvic motion during the test and the knee of the tested side is pushed into adduction to place a stretch on piriformis. If there is a short piriformis the degree of adduction will be limited and the patient will report discomfort behind the trochanter.

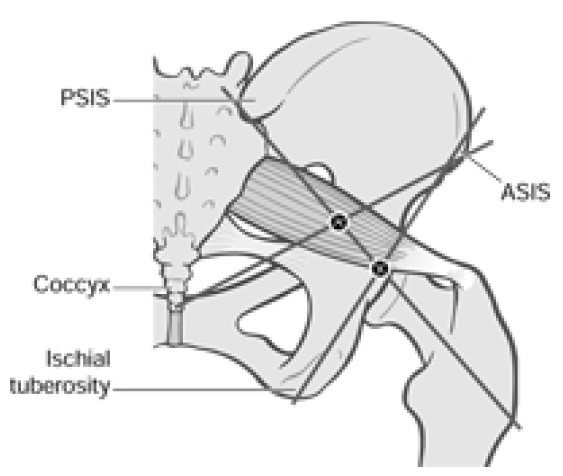

Test (b) Palpation test (Fig. 4.18) The patient is side-lying, tested side uppermost. The practitioner stands at the level of the pelvis in front of and facing the patient, and, in order to contact the insertion of piriformis, draws imaginary lines between:

- ASIS and ischial tuberosity, and

- PSIS and the most prominent point of trochanter.

Where these reference lines cross, just posterior to the trochanter, is the insertion of the muscle, and pressure here will produce marked discomfort if the structure is short or irritated.

Figure 4.18 Using bony landmarks as coordinates the commonest tender areas are located in piriformis, in the belly and at the attachment of the muscle.

If the most common trigger point site in the belly of the muscle is sought, then the line from the ASIS should be taken to the tip of the coccyx rather than to the ischial tuberosity. Pressure where this line crosses the other will access the mid-point of the belly of piriformis where triggers are common. Light compression here which produces a painful response is indicative of a stressed muscle and possibly an active myofascial trigger point.

Piriformis Strength Test

The patient lies prone, both knees flexed to 90°, with practitioner at foot of table grasping lower legs at the limit of their separation (which internally rotates the hip and therefore allows comparison of range of movement permitted by shortened external rotators such as the piriformis).

The patient attempts to bring the ankles together as the practitioner assesses the relative strength of the two legs. Mitchell et al (1979) suggest that if there is relative shortness (as evidenced by the lower leg not being able to travel as far from the mid-line as its pair in this position), and if that same side also tests strong, then MET is called for. If there is shortness but also weakness then the reasons for the weakness need to be dealt with prior to stretching using MET.

Box 4.6 Notes on Piriformis

- Piriformis paradox. The performance of external rotation of the hip by piriformis occurs when the angle of hip flexion is 60° or less. Once the angle of hip flexion is greater than 60° piriformis function changes, so that it becomes an internal rotator of the hip (Gluck & Liebenson 1997, Lehmkuhl & Smith 1983). The implications of this are illustrated in Figures 4.17 and 4.19.

- This postural muscle, like all others which have a predominence of type l fibres, will shorten if stressed. In the case of piriformis, the effect of shortening is to increase its diameter and because of its location this allows for direct pressure to be exerted on the sciatic nerve, which passes under it in 80% of people. In the other 20% the nerve passes through the muscle so that contraction will produce veritable strangulation of the sciatic nerve.

- In addition, the pudendal nerve and the blood vessels of the internal iliac artery, as well as common perineal nerves, posterior femoral cutaneous nerve and nerves of the hip rotators, can all be affected.

- If there is sciatic pain associated with piriformis shortness, then on straight leg raising, which reproduces the pain, external rotation of the hip should relieve it, since this slackens piriformis. (This clue may, however, only apply to any degree if the individual is one of those in whom the nerve actually passes through the muscle.)

- The effects can be circulatory, neurological and functional, inducing pain and paraesthesia of the affected limb as well as alterations to pelvic and lumbar function. Diagnosis usually hinges on the absence of spinal causative factors and the distributions of symptoms from the sacrum to the hip joint, over the gluteal region and down to the popliteal space. Palpation of the affected piriformis tendon, near the head of the trochanter, will elicit pain and the affected leg will probably be externally rotated.

- The piriformis muscle syndrome is frequently characterised by such bizarre symptoms that they may seem unrelated. One characteristic complaint is a persistent, severe, radiating low back pain extending from the sacrum to the hip joint, over the gluteal region and the posterior portion of the upper leg, to the popliteal space. In the most severe cases the patient will be unable to lie or stand comfortably, and changes in position will not relieve the pain. Intense pain will occur when the patient sits or squats since this type of movement requires external rotation of the upper leg and flexion at the knee.

- Compression of the pudendal nerve and blood vessels which pass through the greater sciatic foramen and re-enter the pelvis via the lesser sciatic foramen is possible because of piriformis contracture. Any compression would result in impaired circulation to the genitalia in both sexes. Since external rotation of the hips is required for coitus by women, pain noted during this act could relate to impaired circulation induced by piriformis dysfunction. This could also be a basis for impotency in men. (See also Box 4.7.)

- Piriformis involvement often relates to a pattern of pain which includes: pain near the trochanter; pain in the inguinal area; local tenderness over the insertion behind trochanter; SI joint pain on the opposite side; externally rotated foot on the same side; pain unrelieved by most positions with standing and walking being the easiest; limitation of internal rotation of the leg which produces pain near the hip; and a short leg on the affected side.

- The pain itself will be persistent and radiating, covering anywhere from the sacrum to the buttock, hip and leg including inguinal and perineal areas.

- Bourdillon (1982) suggests that piriformis syndrome and SI joint dysfunction are intimately connected and that recurrent SI problems will not stabilise until hypertonic piriformis is corrected.

- Janda (1996) points to the vast amount of pelvic organ dysfunction to which piriformis can contribute due to its relationship with circulation to the area.

- Mitchell et al (1979) suggest that (as in psoas example above) piriformis shortness should only be treated if it is tested to be short and stronger than its pair. If it is short and weak (see p. 110 for strength test), then whatever is hypertonic and influencing it should be released and stretched first (Mitchell et al 1979). When it tests strong and short, piriformis should receive MET treatment.

- Since piriformis is an external rotator of the hip it can be inhibited (made to test weak) if an internal rotator such as TFL is hypertonic or if its pair is hypertonic, since one piriformis will inhibit the other.

Box 4.7 Notes on Working and Resting Muscles

- Richard (1978) reminds us that a working muscle will mobilise up to 10 times the quantity of blood mobilised by a resting muscle. He points out the link between pelvic circulation and lumbar, ischiatic and gluteal arteries and the chance this allows to engineer the involvement of 2400 square metres of capillaries by using repetitive pumping of these muscles (including piriformis).

- The therapeutic use of this knowledge involves the patient being asked to repetitively contract both piriformis muscles against resistance. The patient is supine, knees bent, feet on the table; the practitioner resists their effort to abduct their flexed knees, using pulsed muscle energy approach (Ruddy’s method) in which two isometrically resisted pulsation/contractions per second are introduced for as long as possible (a minute seems a long time doing this).

Figure 4.19 MET treatment of piriformis with hip fully flexed and externally rotated (see Box 4.6, first bullet point).

Figure 4.20 A combined ischaemic compression (elbow pressure) and MET side-lying treatment of piriformis. The pressure is alternated with isometric contractions/stretching of the muscle until no further gain is achieved.

MET Treatment of Piriformis

Piriformis method (a) Side-lying The patient is side-lying, close to the edge of the table, affected side uppermost, both legs flexed at hip and knee. The practitioner stands facing the patient at hip level.

The practitioner places his cephalad elbow tip gently over the point behind trochanter, where piriformis inserts. The patient should be close enough to the edge of the table for the practitioner to stabilise the pelvis against his trunk (Fig. 4.20). At the same time, the practitioner’s caudad hand grasps the ankle and uses this to bring the upper leg/hip into internal rotation, taking out all the slack in piriformis.

A degree of inhibitory pressure (sufficient to cause discomfort but not pain) is applied via the elbow for 5–7 seconds while the muscle is kept at a reasonable but not excessive degree of stretch. The practitioner maintains contact on the point, but eases pressure, and asks the patient to introduce an isometric contraction (25% of strength for 5–7 seconds) to piriformis by bringing the lower leg towards the table against resistance. (The same acute and chronic rules as discussed previously are employed, together with cooperative breathing if appropriate, see Box 4.2.)

After the contraction ceases and the patient relaxes, the lower limb is taken to its new resistance barrier and elbow pressure is reapplied. This process is repeated until no further gain is achieved.

Piriformis method (b)1 This method is a variation on the method advocated by TePoorten (1960) which calls for longer and heavier compression, and no intermediate isometric contractions.

In the first stage of TePoorten’s method the patient lies on the non-affected side with knees flexed and hip joints flexed to 90°.The practitioner places his elbow on the piriformis musculotendinous junction and a steady pressure of 20–30 lb (9–13 kg) is applied. With his other hand he abducts the foot so that it will force an internal rotation of the upper leg.

The leg is held in this rotated position for periods of up to 2 minutes. This procedure is repeated two or three times. The patient is then placed in the supine position and the affected leg is tested for freedom of both external and internal rotation.

Piriformis method (b)2 The second stage of TePoorten’s treatment is performed with the patient supine with both legs extended. The foot of the affected leg is grasped and the leg is flexed at both the knee and the hip. As knee and hip flexion is performed the practitioner turns the foot inward, so inducing an external rotation of the upper leg. The practitioner then extends the knee, and simultaneously turns the foot outward, resulting in an internal rotation of the upper leg.

During these procedures the patient is instructed to partially resist the movements introduced by the practitioner (i.e. the procedure becomes an isokinetic activity). This treatment method, repeated two or three times, serves to relieve the contracture of the muscles of external and internal hip rotation.

Piriformis method (c) A series of MET isometric contractions and stretches can be applied with the patient prone and the affected side knee flexed. The hip is rotated internally by the practitioner using the foot as a lever to ease it laterally, so putting piriformis at stretch. Acute and chronic guidelines described earlier are used to determine the appropriate starting point for the contraction (at the barrier for acute and short of it for chronic).

The patient attempts to lightly bring the heel back towards the midline against resistance (avoiding strong contractions to avoid knee strain in this position) and this is held for 7–10 seconds. After release of the contraction the hip is rotated further to move piriformis to or through the barrier, as appropriate. Application of inhibitory pressure to the attachment or belly of piriformis is possible via thumb, if deemed necessary.

Piriformis method (d) A general approach which balances muscles of the region, as well as the pelvic diaphragm, is achieved by having the patient squat while the practitioner stands and stabilises both shoulders, preventing the patient from rising as this is attempted, while the breath is held. After 7–10 seconds the effort is released; a deeper squat is performed, and the procedure is repeated several times.

Piriformis method (e) This method is based on the test position (see Fig. 4.17) and is described by Lewit (1992). With the patient supine, the treated leg is placed into flexion at the hip and knee, so that the foot rests on the table lateral to the contralateral knee (the leg on the side to be treated is crossed over the other, straight, leg). The angle of hip flexion should not exceed 60° (see notes on piriformis, Box 4.6, for explanation).

The practitioner places one hand on the contralateral ASIS to prevent pelvic motion, while the other hand is placed against the lateral flexed knee as this is pushed into resisted abduction to contract piriformis for 7–10 seconds. Following the contraction the practitioner eases the treated side leg into adduction until a sense of resistance is noted; this is held for 10–30 seconds.

Piriformis method (f) Since contraction of one piriformis inhibits its pair, it is possible to self-treat an affected short piriformis by having the patient lie up against a wall with the non-affected side touching it, both knees flexed (modified from Retzlaff 1974). The patient monitors the affected side by palpating behind the trochanter, ensuring that no contraction takes place on that side.

After a contraction lasting 10 seconds or so of the non-affected side (the patient presses the knee against the wall), the patient moves away from the wall and the position described for piriformis test (see Fig. 4.17) above is adopted, and the patient pushes the affected side knee into adduction, stretching piriformis on that side. This is repeated several times.

Dr. Alex Jimenez offers an additional assessment and treatment of the hip flexors as a part of a referenced clinical application of neuromuscular techniques by Leon Chaitow and Judith Walker DeLany. The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic and spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

By Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Wellness

Overall health and wellness are essential towards maintaining the proper mental and physical balance in the body. From eating a balanced nutrition as well as exercising and participating in physical activities, to sleeping a healthy amount of time on a regular basis, following the best health and wellness tips can ultimately help maintain overall well-being. Eating plenty of fruits and vegetables can go a long way towards helping people become healthy.

WELLNESS TOPIC: EXTRA EXTRA: Managing Workplace Stress

Post Disclaimer

Professional Scope of Practice *

The information on this blog site is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified healthcare professional or licensed physician and is not medical advice. We encourage you to make healthcare decisions based on your research and partnership with a qualified healthcare professional.

Blog Information & Scope Discussions

Welcome to El Paso's Premier Wellness and Injury Care Clinic & Wellness Blog, where Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, FNP-C, a board-certified Family Practice Nurse Practitioner (FNP-BC) and Chiropractor (DC), presents insights on how our team is dedicated to holistic healing and personalized care. Our practice aligns with evidence-based treatment protocols inspired by integrative medicine principles, similar to those found on this site and our family practice-based chiromed.com site, focusing on restoring health naturally for patients of all ages.

Our areas of chiropractic practice include Wellness & Nutrition, Chronic Pain, Personal Injury, Auto Accident Care, Work Injuries, Back Injury, Low Back Pain, Neck Pain, Migraine Headaches, Sports Injuries, Severe Sciatica, Scoliosis, Complex Herniated Discs, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Pain, Complex Injuries, Stress Management, Functional Medicine Treatments, and in-scope care protocols.

Our information scope is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, physical medicine, wellness, contributing etiological viscerosomatic disturbances within clinical presentations, associated somato-visceral reflex clinical dynamics, subluxation complexes, sensitive health issues, and functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions.

We provide and present clinical collaboration with specialists from various disciplines. Each specialist is governed by their professional scope of practice and their jurisdiction of licensure. We use functional health & wellness protocols to treat and support care for the injuries or disorders of the musculoskeletal system.

Our videos, posts, topics, subjects, and insights cover clinical matters and issues that relate to and directly or indirectly support our clinical scope of practice.*

Our office has made a reasonable effort to provide supportive citations and has identified relevant research studies that support our posts. We provide copies of supporting research studies available to regulatory boards and the public upon request.

We understand that we cover matters that require an additional explanation of how they may assist in a particular care plan or treatment protocol; therefore, to discuss the subject matter above further, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC, or contact us at 915-850-0900.

We are here to help you and your family.

Blessings

Dr. Alex Jimenez DC, MSACP, APRN, FNP-BC*, CCST, IFMCP, CFMP, ATN

email: coach@elpasofunctionalmedicine.com

Licensed as a Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) in Texas & New Mexico*

Texas DC License # TX5807

New Mexico DC License # NM-DC2182

Licensed as a Registered Nurse (RN*) in Texas & Multistate

Texas RN License # 1191402

ANCC FNP-BC: Board Certified Nurse Practitioner*

Compact Status: Multi-State License: Authorized to Practice in 40 States*

Graduate with Honors: ICHS: MSN-FNP (Family Nurse Practitioner Program)

Degree Granted. Master's in Family Practice MSN Diploma (Cum Laude)

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card