Doctors define chronic pain, as any pain that lasts for 3 to 6 months or more. The pain effects an individual’s mental health and day to day life. Pain comes from a series of messages that run through the nervous system. Depression seems to follow pain. It causes severe symptoms that affect how an individual feels, thinks, and how the handle daily activities, i.e. sleeping, eating and working. Chiropractor, Dr. Alex Jimenez delves into potential biomarkers that can help in finding and treating the root causes of pain and chronic pain.

- The first step in successful pain management is a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment.

- The extent of organic pathology may not be accurately reflected in the pain experience.

- The initial assessment can be used to identify areas that require more in-depth evaluation.

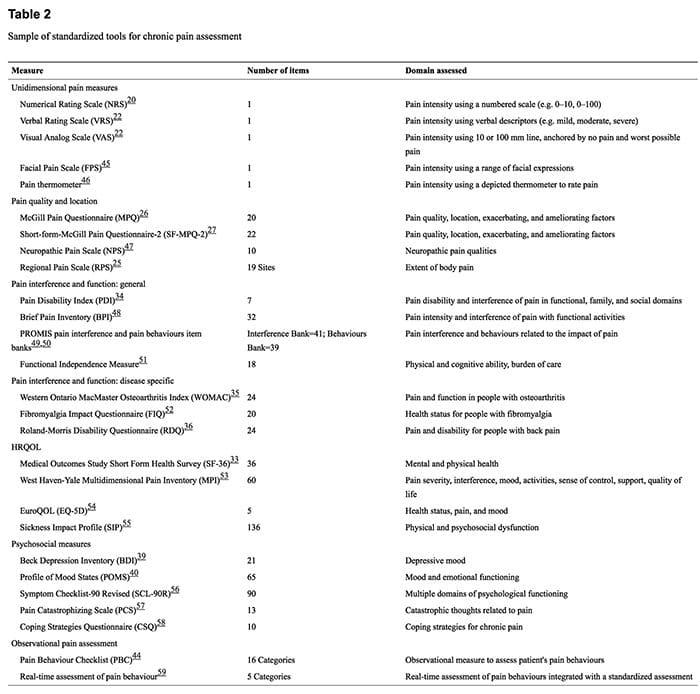

- Many validated self-report tools are available to assess the impact of chronic pain.

Table of Contents

Assessment Of Patients With Chronic Pain

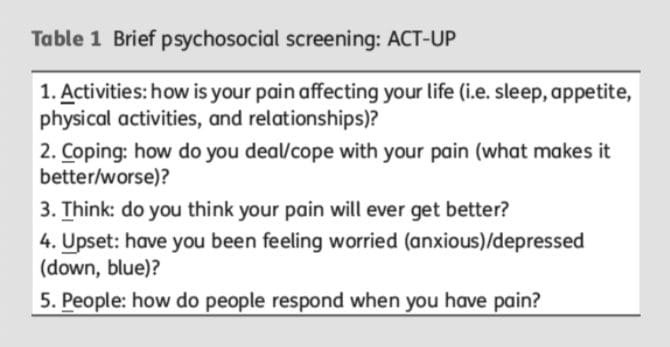

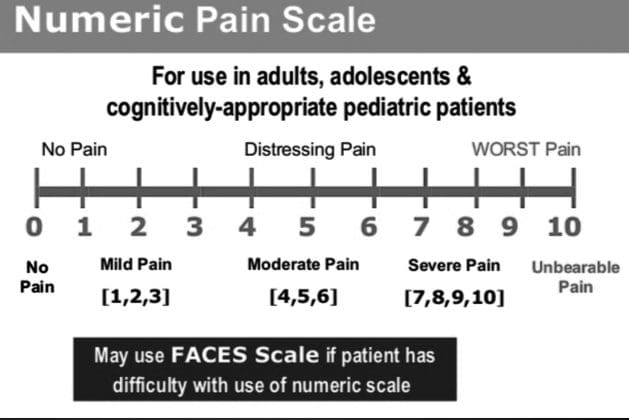

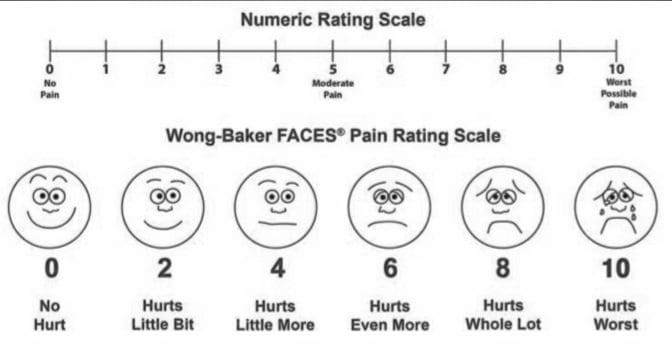

Chronic pain is a public health concern affecting 20–30% of the population of Western countries. Although there have been many scientific advances in the understanding of the neurophysiology of pain, precisely assessing and diagnosing a patient’s chronic pain problem is not straightforward or well-defined. How chronic pain is conceptualized influences how pain is evaluated and the factors considered when making a chronic pain diagnosis. There is no one-to-one relationship between the amount or type of organic pathology and pain intensity, but instead, the chronic pain experience is shaped by a myriad of biomedical, psychosocial (e.g. patients’ beliefs, expectations, and mood), and behavioral factors (e.g. context, responses by significant others). Assessing each of these three domains through a comprehensive evaluation of the person with chronic pain is essential for treatment decisions and to facilitate optimal outcomes. This evaluation should include a thorough patient history and medical evaluation and a brief screening interview where the patient’s behavior can be observed. Further assessment to address questions identified during the initial evaluation will guide decisions as to what additional assessments, if any, may be appropriate. Standardized self-reported instruments to evaluate the patient’s pain intensity, functional abilities, beliefs and expectations, and emotional distress are available, and can be administered by the physician, or a referral for in depth evaluation can be made to assist in treatment planning.

Pain is an extremely prevalent symptom. Chronic pain alone is estimated to affect 30% of the adult population of the USA, upwards of 100 million adults.1

Despite the soaring cost of treating people with chronic pain, relief for many remains elusive and complete elimination of pain is rare. Although there have been substantial advances in the knowledge of the neurophysiology of pain, along with the development of potent analgesic medications and other innovative medical and surgical interventions, on average the amount of pain reduction by available procedures is 30–40% and this occurs in fewer than one-half of treated patients.

The way we think about pain influences the way in which we go evaluate pain. Assessment begins with history and physical examination, followed, by laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging procedures in an attempt to identify and/or confirm the presence of any underlying pathology causing the symptom/s or the pain generator.

In the absence of identifiable organic pathology, the healthcare provider may assume that the report of symptoms stems from psychological factors and may request a psychological evaluation to detect the emotional factors underlying the patient’s report. There is duality where the report of symptoms are attributed to either somatic or psychogenic mechanisms.

As an example, the organic bases for some of the most common and recurring acute (e.g. headache)3 and chronic [e.g. back pain, fibromyalgia (FM)] pain problems are largely unknown,4,5 while on the other hand, asymptomatic individuals may have structural abnormalities such as herniated discs that would explain pain if it were present.6,7 There is a lacking in adequate explanations for patients with no identified organic pathology who report severe pain and pain-free individuals with significant, objective pathology.

Chronic pain affects more than just the individual patient, but also his or her significant others (partners, relatives, employers and co-workers and friends), making appropriate treatment essential. Satisfactory treatment can only come from comprehensive assessment of the biological aetiology of the pain in conjunction with the patient’s specific psychosocial and behavioral presentation, including their emotional state (e.g. anxiety, depression, and anger), perception and understanding of symptoms, and reactions to those symptoms by significant others.8,9 A key premise is that multiple factors influence the symptoms and functional limitations of individuals with chronic pain. Therefore, a comprehensive assessment is needed that addresses biomedical, psychosocial, and behavioral domains, as each contributes to chronic pain and related disability.10,11

Comprehensive Assessment Of An Individual With Chronic Pain

Turk and Meichenbaum12 suggested that three central questions should guide assessment of people who report pain:

- What is the extent of the patient’s disease or injury (physical impairment)?

- What is the magnitude of the illness? That is, to what extent is the patient suffering, disabled, and unable to enjoy usual activities?

- Does the individual’s behavior seem appropriate to the disease or injury, or is there any evidence of symptom amplification for any of a variety of psychological or social reasons (e.g. benefits such as positive attention, mood-altering medications, financial compensation)?

To answer these questions, information should be gathered from the patient by history and physical examination, in combination with a clinical interview, and through standardized assessment instruments. Healthcare providers need to seek any cause(s) of pain through physical examination and diagnostic tests while concomitantly assessing the patient’s mood, fears, expectancies, coping efforts, resources, responses of significant others, and the impact of pain on the patients’ lives.11 In short, the healthcare provider must evaluate the ‘whole person’ and not just the pain.

The general goals of the history and medical evaluation are to:

(i) determine the necessity of additional diagnostic testing

(ii) determine if medical data can explain the patient’s symptoms, symptom severity, and functional limitations

(iii) make a medical diagnosis

(iv) evaluate the availability of appropriate treatment

(v) establish the objectives of treatment

(vi) determine the appropriate course for symptom management if a complete cure is not possible.

Significant numbers of patients that report chronic pain demonstrate no physical pathology using plain radiographs, computed axial tomography scans, or electromyography (an extensive literature is available on physical assessment, radiographic and laboratory assessment procedures to determine the physical basis of pain),17 making a precise pathological diagnosis difficult or impossible.

Despite these limitations, the patient’s history and physical examination remain the basis of medical diagnosis, can provide a safeguard against over-interpreting findings from diagnostic imaging that are largely confirmatory, and can be used to guide the direction of further evaluation efforts.

In addition, patients with chronic pain problems often consume a variety of medications.18 It is important to discuss a patient’s current medications during the interview, as many pain medications are associated with side-effects that may cause or mimic emotional distress.19 Healthcare providers should not only be familiar with medications used for chronic pain, but also with side-effects from these medications that result in fatigue, sleep difficulties, and mood changes to avoid misdiagnosis of depression.

In addition, patients with chronic pain problems often consume a variety of medications.18 It is important to discuss a patient’s current medications during the interview, as many pain medications are associated with side-effects that may cause or mimic emotional distress.19 Healthcare providers should not only be familiar with medications used for chronic pain, but also with side-effects from these medications that result in fatigue, sleep difficulties, and mood changes to avoid misdiagnosis of depression.

The use of daily diaries is believed to be more accurate as they are based on real-time rather than recall. Patients may be asked to maintain regular diaries of pain intensity with ratings recorded several times each day (e.g. meals and bedtime) for several days or weeks and multiple pain ratings can be averaged across time.

One problem noted with the use of paper-and-pencil diaries is that patients may not follow the instruction to provide ratings at specified intervals. Rather, patients may complete diaries in advance (‘fill forward’) or shortly before seeing a clinician (‘fill backward’),24 undermining the putative validity of diaries. Electronic diaries have gained acceptance in some research studies to avoid these problems.

Research has demonstrated the importance of assessing overall health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in chronic pain patients in addition to function.31,32 There are a number of well established, psychometrically supported HRQOL measures [Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36)],33 general measures of physical functioning [e.g. Pain Disability Index (PDI)],34 and disease-specific measures [e.g. Western Ontario MacMaster Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC);35 Roland-Morris Back Pain Disability Questionnaire (RDQ)]36 to assess function and quality of life.

Disease-specific measures are designed to evaluate the impact of a specific condition (e.g. pain and stiffness in people with osteoarthritis), whereas generic measures make it possible to compare physical functioning associated with a given disorder and its treatment with that of various other conditions. Specific effects of a disorder may not be detected when using a generic measure; therefore, disease-specific measures may be more likely to reveal clinically important improvement or deterioration in specific functions as a result of treatment. General measures of functioning may be useful to compare patients with a diversity of painful conditions. The combined use of disease-specific and generic measures facilitates the achievement of both objectives.

The presence of emotional distress in people with chronic pain presents a challenge when assessing symptoms such as fatigue, reduced activity level, decreased libido, appetite change, sleep disturbance, weight gain or loss, and memory and concentration deficits, as these symptoms can be the result of pain, emotional distress, or treatment medications prescribed to control pain.

Instruments have been developed specifically for pain patients to assess psychological distress, the impact of pain on patients’ lives, feeling of control, coping behaviors, and attitudes about disease, pain, and healthcare providers.17

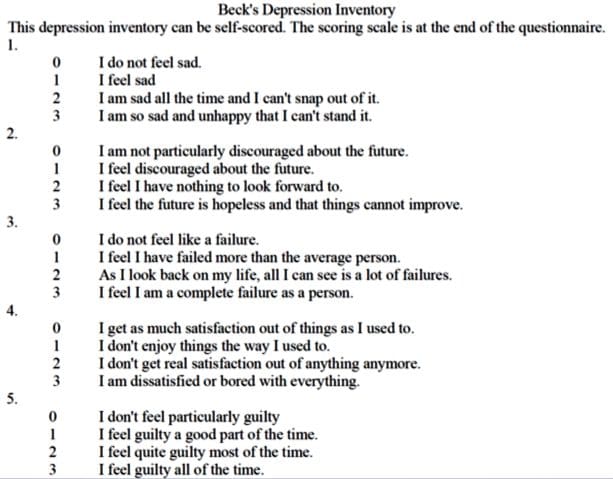

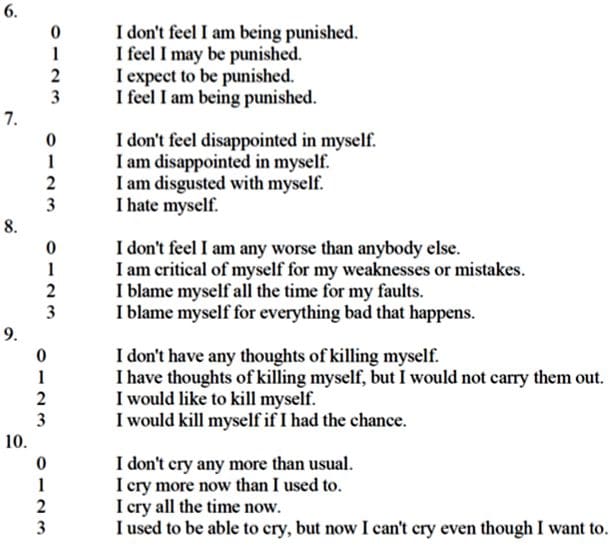

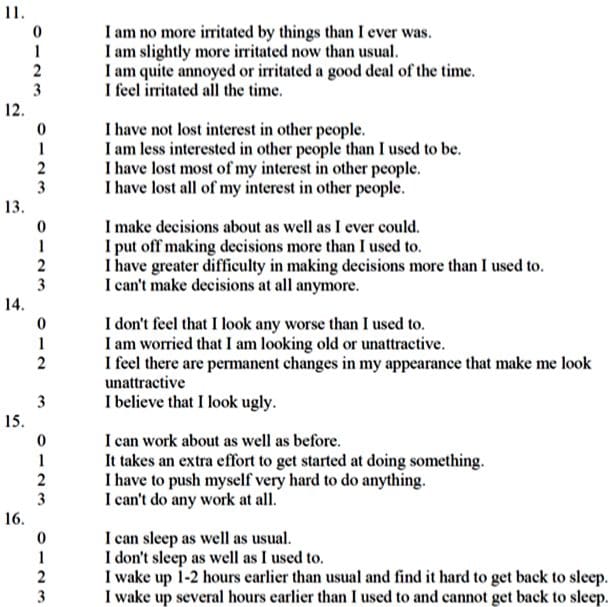

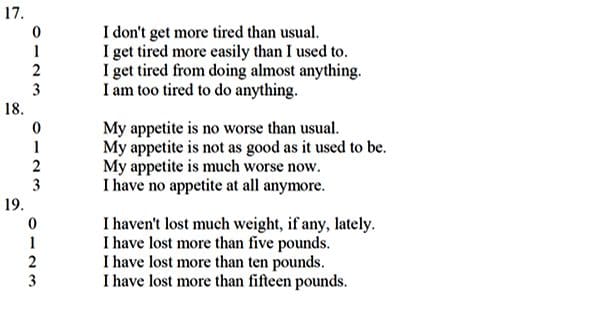

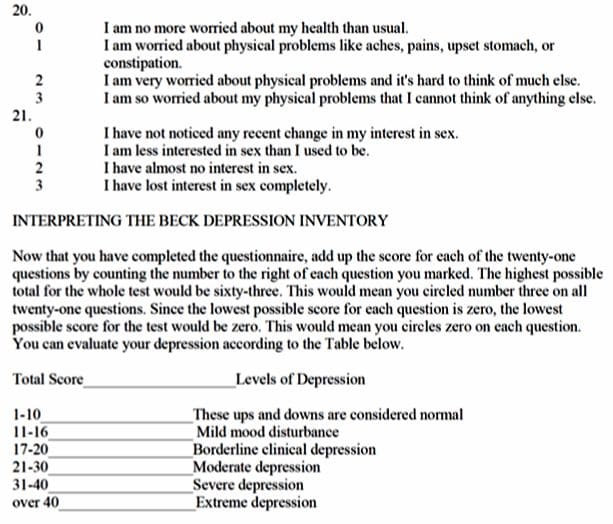

For example, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)39 and the Profile of Mood States (POMS)40 are psychometrically sound for assessing symptoms of depressed mood, emotional distress, and mood disturbance, and have been recommended to be used in all clinical trials of chronic pain;41 however, the scores must be interpreted with caution and the criteria for levels of emotional distress may need to be modified to prevent false positives.42

Lab Biomarkers For Pain

Lab Biomarkers For Pain

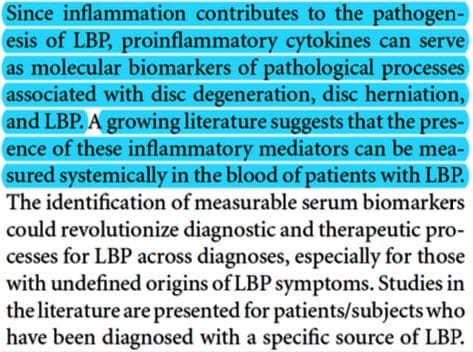

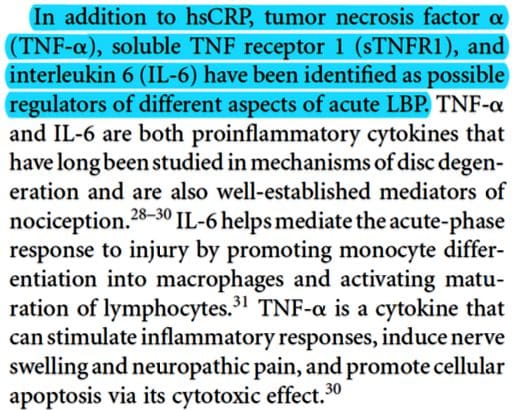

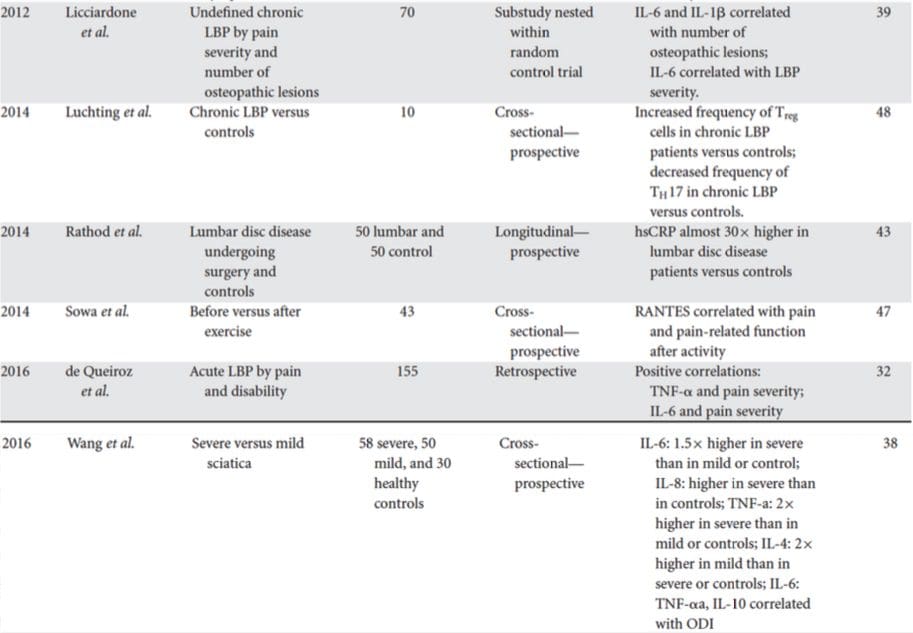

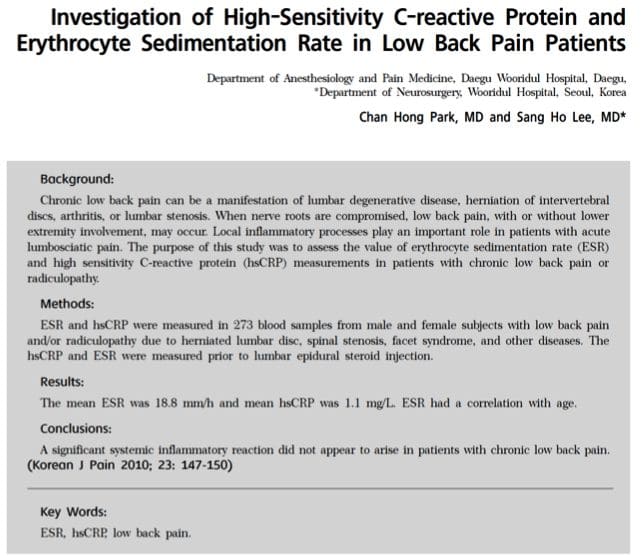

Biomarkers are biological characteristics that can be used to indicate health or disease. This paper reviews studies on biomarkers of low back pain (LBP) in human subjects. LBP is the leading cause of disability, caused by various spine-related disorders, including intervertebral disc degeneration, disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and facet arthritis. The focus of these studies is inflammatory mediators, because inflammation contributes to the pathogenesis of disc degeneration and associated pain mechanisms. Increasingly, studies suggest that the presence of inflammatory mediators can be measured systemically in the blood. These biomarkers may serve as novel tools for directing patient care. Currently, patient response to treatment is unpredictable with a significant rate of recurrence, and, while surgical treatments may provide anatomical correction and pain relief, they are invasive and costly. The review covers studies performed on populations with specific diagnoses and undefined origins of LBP. Since the natural history of LBP is progressive, the temporal nature of studies is categorized by duration of symptomology/disease. Related studies on changes in biomarkers with treatment are also reviewed. Ultimately, diagnostic biomarkers of LBP and spinal degeneration have the potential to shepherd an era of individualized spine medicine for personalized therapeutics in the treatment of LBP.

Biomarkers For Chronic Neuropathic Pain & Potential Application In Spinal Cord Stimulation

This review was focused on understanding which substances inside the human body increase and decrease with increasing neuropathic pain. We reviewed various studies, and saw correlations between neuropathic pain and components of the immune system (this system defends the body against diseases and infections). Our findings will especially be useful for understanding ways to reduce or eliminate the discomfort, chronic neuropathic pain brings with it. Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) procedure is one of the few fairly efficient remedial treatments for pain. A follow-up study will apply our findings from this review to SCS, in order to understand the mechanism, and further optimize efficaciousness.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-2, IL-33, CCL3, CXCL1, CCR5, and TNF-α, have been found to play significant roles in the amplification of chronic pain states.

After review of various studies relating to pain biomarkers, we found that serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-2, IL-33, CCL3, CXCL1, CCR5, and TNF-α, were significantly up-regulated during chronic pain experience. On the other hand, anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-4 were found to show significant down-regulation during chronic pain state.

Biomarkers For Depression

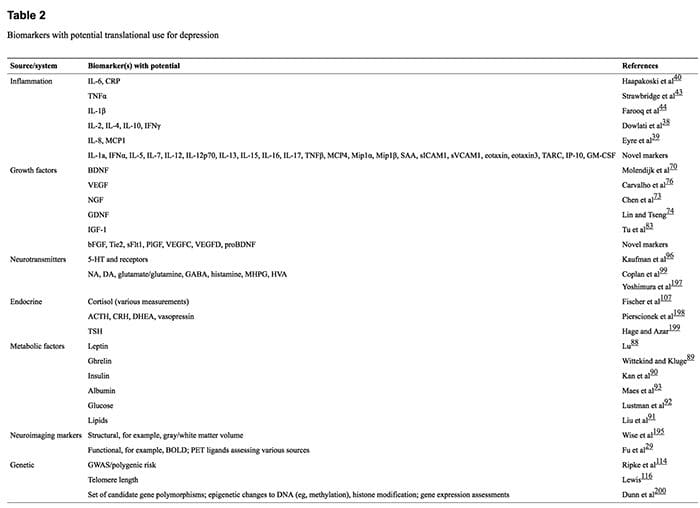

A plethora of research has implicated hundreds of putative biomarkers for depression, but has not yet fully elucidated their roles in depressive illness or established what is abnormal in which patients and how biologic information can be used to enhance diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. This lack of progress is partially due to the nature and heterogeneity of depression, in conjunction with methodological heterogeneity within the research literature and the large array of biomarkers with potential, the expression of which often varies according to many factors. We review the available literature, which indicates that markers involved in inflammatory, neurotrophic and metabolic processes, as well as neurotransmitter and neuroendocrine system components, represent highly promising candidates. These may be measured through genetic and epigenetic, transcriptomic and proteomic, metabolomic and neuroimaging assessments. The use of novel approaches and systematic research programs is now required to determine whether, and which, biomarkers can be used to predict response to treatment, stratify patients to specific treatments and develop targets for new interventions. We conclude that there is much promise for reducing the burden of depression through further developing and expanding these research avenues.

References:

References:

-

Assessment of patients with chronic pain E. J. Dansiet and D. C. Turk*t

- Inflammatory biomarkers of low back pain and disc degeneration: a review.

Khan AN1, Jacobsen HE2, Khan J1, Filippi CG3, Levine M3, Lehman RA Jr2,4, Riew KD2,4, Lenke LG2,4, Chahine NO2,5. - Biomarkers for Chronic Neuropathic Pain and their Potential Application in Spinal Cord Stimulation: A Review

Chibueze D. Nwagwu,1 Christina Sarris, M.D.,3 Yuan-Xiang Tao, Ph.D., M.D.,2 and Antonios Mammis, M.D.1,2 - Biomarkers for depression: recent insights, current challenges and future prospects. Strawbridge R1, Young AH1,2, Cleare AJ1,2.

Post Disclaimer

Professional Scope of Practice *

The information on this blog site is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified healthcare professional or licensed physician and is not medical advice. We encourage you to make healthcare decisions based on your research and partnership with a qualified healthcare professional.

Blog Information & Scope Discussions

Welcome to El Paso's Premier Wellness and Injury Care Clinic & Wellness Blog, where Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, FNP-C, a board-certified Family Practice Nurse Practitioner (FNP-BC) and Chiropractor (DC), presents insights on how our team is dedicated to holistic healing and personalized care. Our practice aligns with evidence-based treatment protocols inspired by integrative medicine principles, similar to those found on this site and our family practice-based chiromed.com site, focusing on restoring health naturally for patients of all ages.

Our areas of chiropractic practice include Wellness & Nutrition, Chronic Pain, Personal Injury, Auto Accident Care, Work Injuries, Back Injury, Low Back Pain, Neck Pain, Migraine Headaches, Sports Injuries, Severe Sciatica, Scoliosis, Complex Herniated Discs, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Pain, Complex Injuries, Stress Management, Functional Medicine Treatments, and in-scope care protocols.

Our information scope is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, physical medicine, wellness, contributing etiological viscerosomatic disturbances within clinical presentations, associated somato-visceral reflex clinical dynamics, subluxation complexes, sensitive health issues, and functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions.

We provide and present clinical collaboration with specialists from various disciplines. Each specialist is governed by their professional scope of practice and their jurisdiction of licensure. We use functional health & wellness protocols to treat and support care for the injuries or disorders of the musculoskeletal system.

Our videos, posts, topics, subjects, and insights cover clinical matters and issues that relate to and directly or indirectly support our clinical scope of practice.*

Our office has made a reasonable effort to provide supportive citations and has identified relevant research studies that support our posts. We provide copies of supporting research studies available to regulatory boards and the public upon request.

We understand that we cover matters that require an additional explanation of how they may assist in a particular care plan or treatment protocol; therefore, to discuss the subject matter above further, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC, or contact us at 915-850-0900.

We are here to help you and your family.

Blessings

Dr. Alex Jimenez DC, MSACP, APRN, FNP-BC*, CCST, IFMCP, CFMP, ATN

email: [email protected]

Licensed as a Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) in Texas & New Mexico*

Texas DC License # TX5807

New Mexico DC License # NM-DC2182

Licensed as a Registered Nurse (RN*) in Texas & Multistate

Texas RN License # 1191402

ANCC FNP-BC: Board Certified Nurse Practitioner*

Compact Status: Multi-State License: Authorized to Practice in 40 States*

Graduate with Honors: ICHS: MSN-FNP (Family Nurse Practitioner Program)

Degree Granted. Master's in Family Practice MSN Diploma (Cum Laude)

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card

Lab Biomarkers For Pain

Lab Biomarkers For Pain References:

References:

Comments are closed.