Muscle strains are a common injury among athletes, together with the hamstrings being susceptible to damage in sports which involve high speed running. As an example, musculotendon strains accounted for almost half of accidents in the National Football League team throughout pre-season practice, with hamstring strains being the most common and requiring the most time (average of 8.3 days) apart from the game.

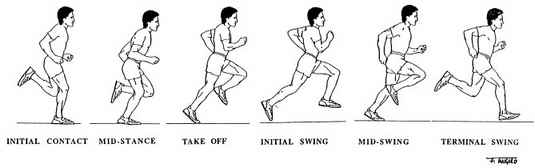

From the Australian Football League, hamstring strains are the most frequent injury with approximately six accidents per club a year, and 33 percent of those being repetitive injuries. The susceptibility of the hamstrings to harm during high-speed running is linked to the biomechanical demands put on the muscle, although debate continues regarding whether the damage occurs through the stance or swing phase of a gait cycle.

This problem is applicable for designing the type of resistance training which may be useful for preventing recurrent or first hamstring injuries, among others. Specifically, injury prevention programs would ideally incorporate aspects (e.g., lower extremity positions, muscle lengths, contraction type) that are most similar to the conditions related to injury, such that the athlete could maximize the gains in functional strength and minimize the risk of future damage or injury.

Table of Contents

Hamstring Injury Research Studies

Animal models have been used to establish relationships between injury threat and musculotendon mechanisms. The degree of muscle trauma includes negative work done by the muscle and the size of fiber strain when stretching a maximally activated muscle. However, when cycles are imposed to a musculotendon unit, the degree of tension can vary which makes the tissue potentially more prone after loading sequences.

These insights are relevant for understanding hamstring injury mechanics. In particular, the biarticular hamstrings are proven to experience a contraction in the quantity of negative work with running speed. Thus, the hamstrings may be vulnerable to some late swing injury because of repetitive strides of high speed. But, other researchers have argued that the hamstrings are more likely to be injured during the stance phase of gait when the limb is subjected to external loading through contact. Also, a recent study suggests that the hamstrings may also experience a lengthening stage during late stance. But there have been no prior studies that have used data to examine kinetics, and limited attempts during sprinting to quantify ground responses.

Other research study results suggest that the hamstrings are considerably loaded during both the stance and swing phases of top speed treadmill running. But, it was also discovered that because the hamstrings undergo a lengthening contraction during swing stage, negative muscle function is restricted to this stage. This result resembles a range of prior kinematic studies, however, contrasts with others, who reported that the athletes experience another lengthening period during the late stance phase of overground running.

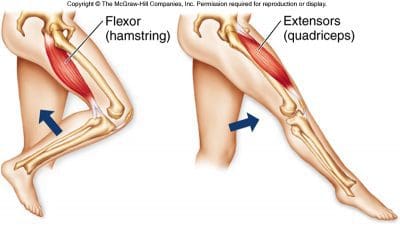

Conceptually, hamstring lengths are primarily a function of knee and hip flexion angles. For example, the hamstrings are lengthening during swing once the hip is bending as these motions both contribute to hamstring stretch and the knee is slowly stretching. However, the hip continues to expand throughout stance and starts to extend before foot contact; the knee then extends until toe-off and flexes until mid-stance. Therefore, if the stretch is to happen during the second half of stance, the hamstring would have to exceed the hamstring shortening because of hip extension. The knee extension speed would have to transcend the hip extension velocity, further because the hamstring muscles at the hip are more substantial than in the knee. But, knee angular velocities and sagittal hip during posture are argued to be of comparable size, making it unlikely that significant hamstring stretch is occurring during stance.

Animal models of muscular injury demonstrated that active lengthening contractions are linked with trauma, which the amount of harm appears to be associated with the negative work done by a maximally activated muscle. In a current study, it was proven that function performed from the hamstrings occurs only suggesting that the chance of a strain injury is higher during swing compared to posture. Hamstring loading was found to increase significantly with pace during swing but not stance, providing support for harm susceptibility. Repeated stretch-shortening cycles are proven to increase the risk of injury in animal models that strides of speed can contribute to the injury threat susceptibility.

Discovering the musculotendon demands during sprinting at the likely time of injury provides direction regarding the sort of resistance training that may prove most valuable in preventing a first or continuing hamstring injury. For example, if an injury occurs during the swing period, then resistance training of the hamstrings might be most successful when performed with lower extremity postures that place the muscle in an elongated position (e.g., hip flexion with knee extension).

Further, lengthening (eccentric) anesthetic beneath inertial load would probably be an essential component of the prevention and rehabilitation plan. This contraction-specificity about injury prevention is supported in studies that demonstrated that the successfulness of a resistance training program. Ultimately, characterizing the load throughout the gait cycle that is sprinting enables the intensity of their resistance training to be scientifically determined.

Conclusion

In conclusion, data indicates that the hamstrings are at higher risk for injury during the late swing phase of high speed running when in comparison to the stance phase. New swing phase is when the biomechanical demands placed on the hamstrings seem most consistent with muscle injury mechanisms. Based on the results from various research studies, a rehabilitation program focusing on particular stretches and exercises is very likely to have a more significant advantage over programs which concentrate on concentric loading of the hamstrings.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic and spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss options on the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900.

By Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Sports Care

Athletes engage in a series of stretches and exercises on a daily basis to prevent damage or injury from their specific sports or physical activities as well as to promote and maintain strength, mobility, and flexibility. However, when injuries or conditions occur as a result of an accident or due to repetitive degeneration, getting the proper care and treatment can change an athlete’s ability to return to play as soon as possible and restore their original health.

Post Disclaimer

Professional Scope of Practice *

The information on this blog site is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified healthcare professional or licensed physician and is not medical advice. We encourage you to make healthcare decisions based on your research and partnership with a qualified healthcare professional.

Blog Information & Scope Discussions

Welcome to El Paso's Premier Wellness and Injury Care Clinic & Wellness Blog, where Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, FNP-C, a board-certified Family Practice Nurse Practitioner (FNP-BC) and Chiropractor (DC), presents insights on how our team is dedicated to holistic healing and personalized care. Our practice aligns with evidence-based treatment protocols inspired by integrative medicine principles, similar to those found on this site and our family practice-based chiromed.com site, focusing on restoring health naturally for patients of all ages.

Our areas of chiropractic practice include Wellness & Nutrition, Chronic Pain, Personal Injury, Auto Accident Care, Work Injuries, Back Injury, Low Back Pain, Neck Pain, Migraine Headaches, Sports Injuries, Severe Sciatica, Scoliosis, Complex Herniated Discs, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Pain, Complex Injuries, Stress Management, Functional Medicine Treatments, and in-scope care protocols.

Our information scope is limited to chiropractic, musculoskeletal, physical medicine, wellness, contributing etiological viscerosomatic disturbances within clinical presentations, associated somato-visceral reflex clinical dynamics, subluxation complexes, sensitive health issues, and functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions.

We provide and present clinical collaboration with specialists from various disciplines. Each specialist is governed by their professional scope of practice and their jurisdiction of licensure. We use functional health & wellness protocols to treat and support care for the injuries or disorders of the musculoskeletal system.

Our videos, posts, topics, subjects, and insights cover clinical matters and issues that relate to and directly or indirectly support our clinical scope of practice.*

Our office has made a reasonable effort to provide supportive citations and has identified relevant research studies that support our posts. We provide copies of supporting research studies available to regulatory boards and the public upon request.

We understand that we cover matters that require an additional explanation of how they may assist in a particular care plan or treatment protocol; therefore, to discuss the subject matter above further, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC, or contact us at 915-850-0900.

We are here to help you and your family.

Blessings

Dr. Alex Jimenez DC, MSACP, APRN, FNP-BC*, CCST, IFMCP, CFMP, ATN

email: [email protected]

Licensed as a Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) in Texas & New Mexico*

Texas DC License # TX5807

New Mexico DC License # NM-DC2182

Licensed as a Registered Nurse (RN*) in Texas & Multistate

Texas RN License # 1191402

ANCC FNP-BC: Board Certified Nurse Practitioner*

Compact Status: Multi-State License: Authorized to Practice in 40 States*

Graduate with Honors: ICHS: MSN-FNP (Family Nurse Practitioner Program)

Degree Granted. Master's in Family Practice MSN Diploma (Cum Laude)

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card

Comments are closed.